The wing of the phalanx was a fearsome “weapon” for the time that was deployed by the Greeks during the Archaic, Classical and Hellenistic period, from the 7th century BC. Until then, ancient armies were exercising simplistic warfare. Usually, the basic unit was a strong equestrian task force (or chariots), who manned the noble course. The duels were among nobles and the losses were kept relatively small (see Homeric epics). The result was a more prestigious victory, more characteristic of “primitive” cultures where the objective was not the complete annihilation of the enemy.

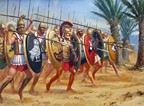

Instead, the phalanx was based on the (usually equal stated) citizens of each city – state. They were pedestrians (numerous cavalry could only be sustained on Thessaly, Macedonia and less on Boeotia) heavy armored and armed. It is understood that the costs of addiction were such that the landless destitute one could not cope with, so the soldiers were free farmers and townsfolk with a steady income. Apart from dependence, the hoplite phalanx was based on the excellent coordination of members and their move in formation. Thanks to them, and despite the heavy weapons, the phalanx could keep its cohesion, moving with some speed and perform the necessary maneuvers. It is understood that there had to be dressage, excellent physical fitness and discipline in the command. Thanks to these characteristics, the convoy that had better cohesion and education could brake and make the opposing phalanx flee, with relatively small losses by both parties. Again it was a conflict of small losses, as there was no well-trained cavalry to kill the fugitives. But when two columns were steady and inseparable, the battle was severe and the losses heavy by both rivals. This phenomenon of bloody fighting intensified since the 5th century BC and then, when the antagonism between the Greek cities became predatory the martial tactics became more and more refined.

A key feature of the phalanx is that the shield of each soldier was protecting only his left side because the right hand had to handle the spear or sword. The unsecured right had to be protected by the shield of the adjacent soldier. Therefore, not everyone was fighting alone but relied on his neighbor, so the unity and mutual support were necessary.

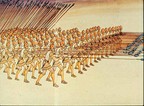

To be resistant to attempts at division, the convoy had to have “depth” of at least some men. A smaller depth enabled large amplitude and thus encircling the opponent (or even preventing the recycling, if the enemy were more numerous). But it lacked resistance and impact strength. Miltiades, to overcome this problem in the battle of Marathon where the Athenians were outnumbered, applied a trick. He reinforced the flanks and weakened the center, and quickly attacked the Persians before they had a chance to break down the completely weakened center of the Greeks.

In some battles, the Boeotians experimented with much greater depths in the center or at one end of the phalanx. To prevent the encirclement (since the other two parts were dangerously weak and of small width), they attacked swiftly with their reinforced part against the most critical part of the enemy camp (where the best soldiers and their leader lied). If they managed to break it, they usually got the win because the opponent’s remaining soldiers panicked and fled. Many times this move was sideways to the opponent in order to surprise them and not hit that part of the enemy bloc that was opposite and therefore did expect the blow.

The importance of phalanx was reduced somewhat by the use of heavy cavalry and other tactics, especially during the 4th century BC. The use of very well trained lightly armed men (professional mercenaries) enabled quick maneuvering thunderous blows in which the heavy and cumbersome on phalanx did not have time to respond. The “peltastes” equipped with long spears, bows, slingshots or other light guns and protected only by a small shield (pelti) and light or no armor, defeated the phalanx soldiers many times, especially on uneven ground where the phalanx lost its coordination easily. The phalanx of Macedonians was a variation where the spear (“sarissa”) allegedly had a length of 6 meters (!). The Macedonians phalanx of soldiers brought light defensive weapons and shield hung by the neck, so they could keep the sarissa with both hands. The forest of spears was enough for them to not need a strong defensive armor, but this phalanx could easily be circled. Philip and Alexander had to use cavalry as a basic striking force and coverage of the phalanx. Instead, the latter Macedonians kings neglected the cavalry. The result was a defeat by the Romans, when they realized the weakness of the Macedonian phalanx lied in its flanks.